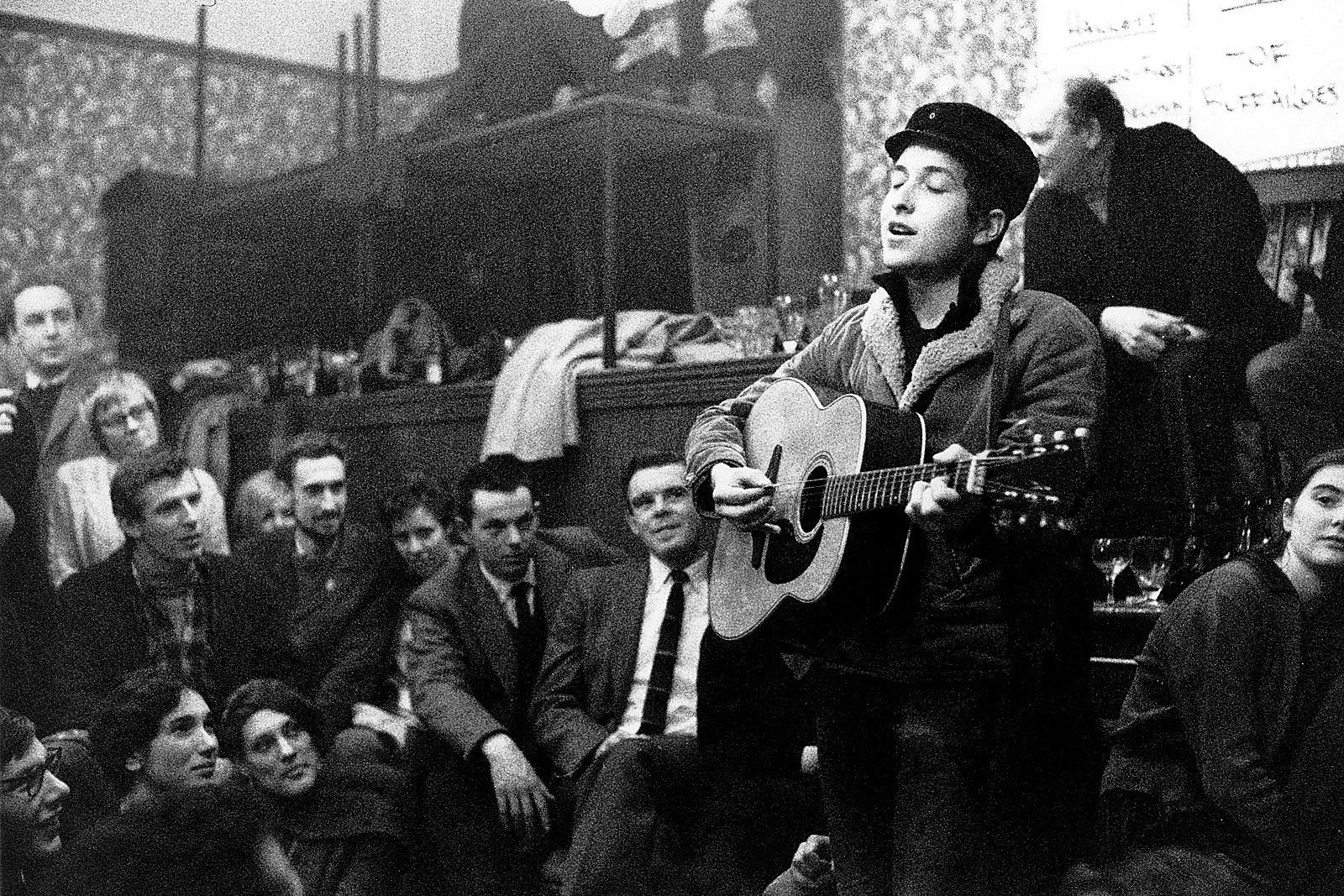

“Blowin’ in the Wind” by Bob Dylan is often described as a protest song. It raises questions about war, peace, freedom, and human dignity. But beneath its historical role lies a more enduring question:

Is it literature?

Songs and poems share a common lineage. Both rely on rhythm and repetition. Both use sound to carry meaning. Both are shaped to linger—long after the moment of hearing has passed. We often privilege poetry as “literary” because it exists on the page, but language does not lose its depth when it is voiced rather than printed.

That boundary blurred publicly in 2016, when Dylan was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for creating “new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition.” The decision unsettled traditional definitions, but it also clarified something essential: literature is not confined to form.

As Harper’s Magazine observed at the time, the literary includes not only what is written, but what is expressed and invented—language that departs from ordinary usage to reveal something human, reflective, and lasting.

Written in 1962, “Blowin’ in the Wind” became an anthem for civil rights and anti-war movements not because it delivered conclusions, but because it refused to. The song offers a sequence of unanswered questions, returning again and again to the same refrain.

How many roads must a man walk down

Before you call him a man?

How many years can some people exist

Before they’re allowed to be free?

How many deaths will it take ’til he knows

That too many people have died?

These lines endure because they do not resolve themselves. They invite reflection rather than agreement. The listener becomes part of the meaning.

If literature helps us notice what we already sense but struggle to articulate, then the question is not whether this song qualifies.

The question is whether we are willing to listen long enough for its meaning to take hold.