When I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings was published in 1969, Angelou was recognized as a new kind of memoirist. She wrote herself into the center of her own story at a time when Black women were rarely allowed that position in literature. As scholar Hilton Als has noted, Black female writers had long been marginalized, their inner lives pushed to the edges. Angelou changed that by speaking plainly, courageously, and without apology.

Her autobiographical work has sometimes been described as autobiographical fiction—not because it distorted truth, but because it stretched beyond the individual. Angelou often wrote in the first person singular while meaning something collective. When she said “I,” she was also saying “we.” In that way, her work echoes the slave narrative tradition and the oral storytelling roots of her poetry, carrying personal experience outward until it became communal truth.

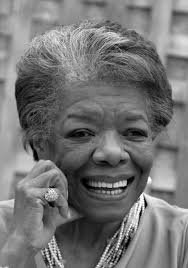

Angelou did not write to comfort readers with easy reassurance. Her poems and reflections were not feel-good platitudes, but lived truths—about fear, survival, love, and resilience—that could be felt as much as read. Her language drew from everyday speech and lived experience, grounding her work in the world rather than above it.

In 2011, Barack Obama awarded Angelou the Presidential Medal of Freedom, recognizing a lifetime of cultural and moral influence. Yet her legacy reminds me that lasting impact is not reserved for the famous. We are remembered, often quietly, by how we make others feel—by whether we listen, whether we care, whether we leave people more human than we found them.

Angelou shaped how I think by showing that personal truth, honestly spoken, can become a shared inheritance—and that bearing witness to one life can help illuminate many.